Life on the Go

The intertidal zone of the sandy beach and its mobile inhabitants are incredibly dynamic. If you dig in the wet sand and find sand crabs, don’t expect to find them in the same place a few hours later. As in all intertidal zones, any given spot in the intertidal zone changes from submerged, at high tide, to exposed, dry conditions during low tide – a radical change in habitat over a short timeframe. What is different about the beach is that many of the animals that live here move constantly to follow the tide as it rises and falls. An array of crustaceans – including sand crabs, roly polies (isopods), and beach hoppers (amphipods) – as well as beetles, blood worms and clams, all move up and down the beach according to the water level. This on-the-go lifestyle makes management of this ecosystem a unique challenge (see Best Practices).

Sand Dwellers Move All over the Beach

Hidden under the sand in temporary burrows or nestled in the kelp wrack, sand dwelling animals associated with different parts of the beach are constantly shifting position with the tide. These small creatures swim, scud, hop and crawl up and down the beach, travelling many meters a day. Their habitat is never confined to one location; they can move any direction on the beach to follow changes in beach width and conditions.

A couple of moving beach “landmarks” known as the “high tide line” and the “water table outcrop”shown here at low tide and high tide can help you locate some characteristic sand dwellers.

The high tide line has animals associated with wrack, including:

- Upper beach isopods (roly polies) burrow from the high tide line and up to older dried wrack piles

- Beetles, including flightless species, in wrack piles (many of these eat fly larvae and beachhoppers)

- Beach-hoppers in burrows in damp sand below and around the high tide (and in fresh wrack)

The water table outcrop (where damp sand meets saturated sand) often has:

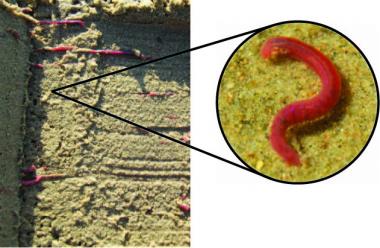

- Bloodworms, Thoracophelia, burrow in damp sand above the water table outcrop

- A fast swimming isopod, Excirolana (a mid-beach isopod) scaveges for food above and below the saturated sand zone

- Sand crabs and clams are found burrowed below the saturated sand. Sand crabs are often visible in feeding aggregations in the swash zone

Sand crabs (aka mole crabs) are bizarre critters. Shaped like small eggs and growing up to 1.5-inch long, these sand dwellers are easily spotted at the beach. They spend their lives following the tides in order to remain shallowly buried in the wave wash. Here, in the wet shoreline sand they ‘fish’ for food with their feathery antennae. They like to stay close together or aggregate; so, look for the textured sand caused by tiny holes in the sand at the water’s edge. You also may be able to see the V-shaped ripples caused by wave wash flowing over the antennae as they seive the water for food. The crabs will quickly retract their antennae when the wave wash retreats or when they feel the vibrations from approaching footsteps. Unlike most crabs, they have no claws and are suspension feeders, eating the plankton caught in their antennae. Sand crabs are amazingly well adapted to move in the sand and swash; they swim and burrow, moving backwards, and constantly rebury themselves as they follow the waves.

Blood worms, named for their red color due to hemoglobin, are commonly found in the mid-intertidal zone near the surface in damp sand exposed at low tide. Look for the numerous tiny holes in the sand that indicate their presence. They eat sand as they burrow, like earthworms, getting food from the accompanying organic material. Their vacuum-like feeding behavior helps to clean and aerate the sand.

A variety of clams live in the lower intertidal zone of sandy beaches, including bean clams, Pismo clams and razor clams. Although harvest limits are low and populations in most sandy beaches are not large enough to support extensive harvesting, clams are harvested both recreationally and commercially for food.

Indicators of Beach Health: Roly Polies and the Upper Beach

On many Southern California shores, the upper beach is disappearing and along with it at least two of its denizens: Tylos punctatus and Alloniscus perconvexus. These isopods (aka roly polies), unlike many critters that live lower on the beach, do not live in the ocean for any part of their life cycle nor can they move long distances as adults. If their habitat is lost they are unable to move to a new location. Once widespread in Southern California, they are now only found at relatively pristine beaches that are not heavily impacted by beach armoring, grooming, and/or nourishment and have limited vehicle access. Generally, beaches where these roly polies are found are home to a list of species with similar life histories and vulnerable to decline; thus, suggesting these isopods are a good indicator of beaches with high biodiversity and other rare species.

There have been local extinctions of these beach-dwelling crustaceans at many beaches in Southern California, especially in Santa Monica Bay and Orange County. As a result, 74% of the remaining populations now live in the Santa Barbara and Zuma littoral cells.

When considering the future impacts of climate change on sandy beaches, the eastern end of the Santa Barbara littoral cell may offer one of the best opportunities for the survival of populations of these increasingly vulnerable beach creatures. Twelve kilometers of mostly undeveloped shoreline provides the rare possibility for shoreline retreat in Southern California. One important opportunity is Ormond Beach in Oxnard, CA.